* Names have been changed to protect the identity of whom this true account is written about

I still remember the day that everything in our lives overturned, and I lost my power of words. I always thought of myself as someone who can elaborate well; Hashem has gifted me with an ability to teach, an ability to explain things. Being a mother of four and an experienced teacher of over twelve years, I always thought I’m one of those lucky ones that has an answer for everything, that Hashem had gifted me with the koach of being able to give over, to break down, and to express any thought or idea.

However, after that day, I found myself at a loss.

My car pulls into the carpool lane, and I see my two daughters standing outside with happy faces. My oldest, Penina, holds her six- year-old sister Chava with one hand, her other hand clutching the briefcase strap that lies on her shoulder.

It is a cold, gray, rainy day. Droplets of rain on the glass are swept away by the windshield wipers. As my van edges closer, I uncontrollably break into violent sobs. I realize why I’m crying- because my girls have no idea that this cold day in November is their last day of school.

I try to suppress my cries, and stifle them as the car door slides open and my girls hop into the car. They are soaking wet from waiting outside, but they are happy. They are in school. That’s all that matters.

While buckling her seat belt, my oldest announces in an excited voice, “Hi, Mommy! Guess what? My Morah said that next week, for Chanukah, we are going to the nursing home to sing Chanukah songs to the Bubbies and Zaidies!”

Holding back my tears, I try to concentrate on the road. My mind is racing and I am fighting to keep my focus. I don’t know how to break it to her and tell her that there never will be a visit to the nursing home. There never will be a lot of anything anymore. The thought of breaking her heart paralyzes me, and I remain silent…

“Mommy, why are you quiet?” my eight- year- old asks.

After a few moments of silence, the younger one responds, “She’s sad.” A pause. She whispers, “I think she’s crying.”

We pull up into the driveway and the door automatically slides open. I help my kids out and in silence, we enter our home. Without even removing my coat, I tell my daughters, “Girls, I want to talk to you about something very important. Come with me.”

I lead them into the living room, I sit down on the couch and they sit next to me, anxiously waiting to hear what is coming next. As I look at my eight- year- old Penina’s meaningful glaze, and my eyes dart to my Chavale’s sweet cheeks, my heart sinks.

“Girls, the menahel called me today. He told me you can’t come to school anymore.” There, I’ve said it.

“What? Why?!” Penina cries out in an alarmed voice.

“Because you don’t have your shots,” I respond. I already feel my breathing becoming irregular, but I try to stay strong. Hashem, please guide me through this.

“But why? I thought we got a letter from our doctor!” Penina responds.

I nod my head. “You’re right. We did give in a medical exemption, but the school decided that they don’t want to accept it. They want us to have a medical exemption only from their school pediatrician, and the school pediatrician doesn’t want to give us one. ”

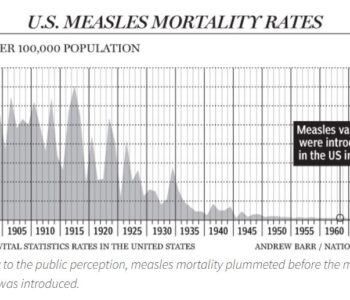

This is part of my frustration. I have a history of a life-threatening reaction to vaccination, and my oldest daughter also had a neurological reaction to vaccines. We were informed by our doctor that there can be a genetic predisposition to adverse reactions, and that for us, it would be better not to vaccinate. Moreover, we had the psak of a gadol that in our case, it is not permitted for us to vaccinate, as for our children, the risk of harm was too great. The school pediatrician was not aware of such a medical view, and although she could not assure me that my children would be safe from any adverse events, she nevertheless insisted that we vaccinate our children or leave the school. I offered to provide her with medical literature that supports our doctor’s view, or to perhaps have a conversation with our doctor, but she refused.

“But we’re not sick!” Chava pipes up with frustration.

I nod my head and have nothing to say.

I don’t know what to say to my three-year-old son, Sruly, when two weeks later his playgroup morah calls me and tells me that word has gotten out about my children being expelled from school, and that since she’s part of the school, she must comply with the school.

“But I want to learn Alef Beis!” he protests. I swallow hard. And I have nothing to say.

I have nothing to say when the following week, my close friend calls me and informs me that my children and I are no longer welcome in her home. She isn’t concerned about us carrying viruses, but feels that other people wouldn’t want to come to her house if she allows us to come. I also stay quiet when she doesn’t speak to me for many months, doesn’t ask how my children and I are doing. When she finally speaks to me, if feels like a police interrogation as she questions my actions, asks nosy questions, yells a mussar shmuz at me and harshly suggests that I should move.

I have nothing to say when children stop coming to my house; when I receive text messages from neighbors on the block that we are no longer welcome in their homes. I didn’t know what to tell my children when my neighbor, who lives in the house across the street from us, makes an upsherin. My children sit by the window, watching longingly, as they watch throngs of children heading to the party, while they were uninvited. I don’t know how to answer my children’s cries of, “Mommy, I want a friend! I want to play with someone!”

My three- year- old begs me, “Mommy, can I please go to Zevy’s house? He’s my best friend!”… But we’ve been explicitly told we are not welcome. I also don’t know how to respond when my daughters come back from B’nos get-togethers on Shabbos, complaining that they’ve been teased for “being fired from school”, and that they were pushed, shoved and potched for not being vaccinated.

For months, day in and day out, I take the responsibility of homeschooling all three of them. Laundry doesn’t get done, dishes aren’t washed, and my infant cries for attention, as I struggle to somehow maintain a structured homeschooling environment and follow through with each child’s curriculum. As a teacher, I have access and knowledge of all the curriculum and worksheets. Not only do I have to create lesson plans and tests for my students at my workplace, but I also have to do so for each of my children.

I can’t explain to you how painful it is to wake up in the morning, and watch other children walking to school in their uniforms, wearing their briefcases. A part of us feels so less than. So… inadequate. Our children are perfectly healthy. And yet, they aren’t allowed to enter our school.

Words can’t express our pain and humiliation. If one were to see us, they would see a lady with a short sheitel, a skirt well past her knees, and conservative dress, and a pashut kollel yungerman with a beard, a black hat, white shirt and black suit jacket. We are simple, non-materialistic people. Community is so important to us, because we have no family. My husband is a yasom, and my parents live in a different part of the world and are not close to us. To us, our neighbors and rabbonim are our family. To be ostracized from the community and to lose our friends causes tremendous shame, isolation, and loneliness.

When somebody tells my husband that of all the families that are persecuted for choosing not to vaccinate, the “baalei teshuva are the ones that have it the worst”, I see the look of sadness that falls across my husband’s face. We are brokenhearted and dejected at the thought that maybe this is true… that because we don’t have a “name” or money, then perhaps, we are “nobodies”. My husband and I just look at each other, our eyes meeting each other’s gaze, and sit… once again…in silence. We have nothing to say.

I have nothing to say when we plead with the school to allow us to present our case to the V’aad; they tell us “There is no V’aad anymore. We asked our shaila to a Daas Torah.” When we ask to be permitted to present our case to the daas Torah, we were told that the identity of the Daas Torah will not be disclosed to us, and that any further conversation must be taken up with the school attorney.

When we contact the school attorney, he yells at us that not vaccinating is “reprehensible” and that he refuses to converse with us unless we hire an attorney. We are stunned. After several months, out of desperation, we finally hired a lawyer to attempt to at least have a conversation with the “other side”, to sit down with them and attempt to negotiate to at least finish off the school year. Our attorney informs us that the school attorney, a frum Yid, spoke very disrespectfully about us, referring to us as “jerks” and describing us as “leprosy-carrying” and “disease infested”.

I don’t know how to explain it to my children when we plead with rabbonim to help us, however, they all turn away and tell us they aren’t going to get involved. One of them is even responsible for suggesting to our Sruly’s playgroup morah to kick him out. We beg him to have a two-way conversation with us regarding this issue, and we plead with him to speak to rabbonim and doctors that are knowledgeable in this area. Our pleas fall onto deaf ears, and we are denied any platform to speak.

I don’t know what to say when my Penina asked me, “Mommy, isn’t our Rav supposed to be like a father to us? Isn’t he supposed to take care of us?” Their emunas chachamim is being challenged, and I have no answer.

I don’t know what to say when the city’s most prominent posek comes knocking on our door one erev Shabbos, urging us to pack up and leave town. My children stand by the staircase, witnessing the scene, listening to him tell us that people like us are not “wanted in a pro-vax town”. We asked him, “Move? How can we just pick up and move? Who will pay for a new house? Who will help us with our move?” The rav responds, “I’m sure you’ll find a way, just like everyone else does.”

“Mommy, why does the rebbe want us to move?” Chava’le asks me. I don’t know what to say.

My husband doesn’t know what to say when late at night, he finds my daughter’s handwriting scribbled on a blue Post-It stuck on the table where he learns. “Dear Totty, I know I don’t say it much, but I feel it in my heart. I’m really sad. I don’t have any more friends because I don’t have shots. I don’t want to live here anymore. I want to move away from here.”

Eventually, things take a turn for the worse when my husband is informed by his Rosh Kollel that he has received phone calls from members of the community requesting that he be expelled from the kollel because he is a “rodef” because he may be carrying my children’s “viruses”. We are also eventually banned from six shuls, mikvaos and gemachs. Signs are posted outside of these places, exposing us and humiliating us to the public.

My children and I continue to face degradation when our neighbor, who purchased a new pool for her backyard and allows all the children on our block to swim, tells my children that they are not permitted to use the pool because they are “dangerous”.

My husband and I have made the decision to move out of the town that we used to know and love so much. We are leaving with our heads down and with feelings of grief, dejection, and fear of trusting others in klal yisroel.

I find myself drained from the constant tefillos and tears I have shed over this, to the point where only my heart can express what my neshama has to say, as my words have been frozen. Sometimes I catch myself davening in the middle of my sleep, for the most part having nothing to say but “Please, Hashem…”

At this point, I ask of whoever’s reading- if I have no words… if I am unable to speak for myself, can someone out there please find the words to speak for us? Can someone perhaps hear my silent cry, and to perhaps speak for me…for US; for the countless hundreds of Yiddishe families that have suffered in silence? At the very time when all of us have nothing to say, can somebody have the ability to combat the sinas chinam with tremendous ahavas chinam?

Will there be a brave one that can be courageous enough to take a stand to help a family- and all the other families- that have been shamed, humiliated, betrayed and destroyed; can someone stop the madness and help these families recover from the trauma that they have experienced?

Will someone raise their voices for the sake of the children’s ruchnius, not just for the learning that they have missed out on, but for the injustice their neshamos have received from our own communities? Can someone find a way to reinstate our children’s emunas chachamim and restore our faith in our own people?

What will we tell our children when we look back at this important time and point of our history? Did we remain SILENT?